|

HOME |

Papermaking The river provided a reliable source of power all year round for the paper mills to run their beating machines to turn cloth rags into pulp, and there was a significant demand for paper locally and in nearby London. It was not surprising therefore that many of the millers along the valley, who had traditionally relied on flour production, converted their mills to produce paper when the market for flour was transformed by new technology that threatened to drive them out of business. In our modern times where paper production is in massive demand most paper is made from wood pulp. There has been a steady increase in paper recycling, and on this page we have a section on HOW TO MAKE YOUR OWN RECYCLED PAPER. |

Wey WEY NATURE |

|

||

|

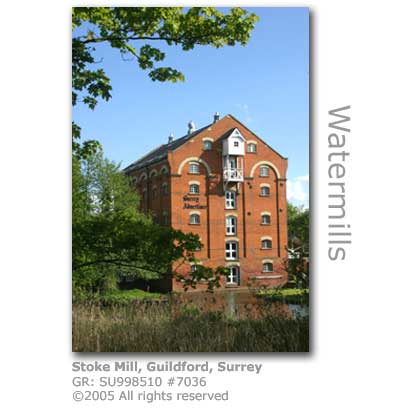

A Short History Papermaking was originally developed in India and China reaching Britain via Arab and Spanish traders. The first British paper mill was recorded in Hertford in 1488, with Godalming being the first in Surrey during the reign of James I (1603 – 1625). Stoke Mill was the first to produce paper in Guildford in 1653. It's quite fitting that the headquarters of the Surrey Advertiser is now based here. The valley along the Wey Navigations proved to be a good location for papermaking providing long-term viability for the industry. The process needed a good and dependable supply of quality rags, clean water, water power to drive the beating engines, and a pool of skilled craftsmen all of which was fulfilled along the Navigations. The Wey also had the benefit of a strong regional market for its paper, and London was only 20 miles or so away.. Traditionally paper was made from rags that had been allowed to ferment and that were then beaten to a pulp by hammers. The pulp, known as 'stuff' was then used to form the paper fibres. The early output of commercially produced paper in the Wey Valley was of ‘whited-brown paper’, a coarse brown paper, with the higher quality writing paper having to be imported from the more technically advanced mills in Europe. The paper milling industry was to be transformed when in the late 17th century Dutch and French papermakers emigrated to England, and the Company of White Paper Makers was incorporated and was granted a monopoly to produce writing and printing papers. One of the Company’s members’ mills was on the River Wey in Byfleet, and this account of the papermaker’s craft was made by John Evelyn in 1678:

In the first half of the 18th century more efficient machines for making pulp were imported from Holland. The Hollander, as it was fittingly called, consisted of an oval trough 10 feet (3 metres) long in which a mixture of water and rags was churned and macerated by an adjustable iron roller with projecting blades. Earlier machines had used water-powered hammers or ‘stampers’ similar to those used in the gunpowder mills. By the end of the 18th century new inventions were to transform the paper making industry driving many of the smaller mills out of business in the process. The discovery of chlorine enabled the natural off-colour of the stuff to be bleached whiter. The Fourdrinier paper-making machine produced continuous rolls of paper rather than individual sheets, and considerably improved the speed of production. In this new process the stuff flowed from a vat onto a continuously moving web of wire. This then moved around a series of drying rollers before being reeled as paper. The reel paper was then cut to size. Steam engines were installed in some mills to supplement water power for driving the beating engines for stuff production. Both mechanical innovations were expensive and could be afforded by wealthy mill owners only, which was to result in considerable consolidation of production in the industry. In the 1860s rags were replaced by new materials, esparto grass and wood pulp, both of which were imported and so mills closer to the Thames and the coast were to benefit.

Papermaking was still a viable concern in the 1830s in Chilworth, Postford in Albury, Westbrook in Godalming and Stoke in Guildford. The Chilworth and Postford mills had ceased production by the early 1870s. The last paper mill in Surrey was at Catteshall in Godalming which didn’t close until 1928. The early paper mills along the Wey Valley were quite prolific: An interesting artefact of the papermaking era is the heavy roller, that until recently was used by Blackheath Cricket Club to roll their greens. This started life as a cylinder from a papermaking machine at nearby Chilworth papermills.

How Paper Was Made White linen or cotton rags were used to make good quality paper, and coarse rags were used to produce the rougher brown paper. The creamy pulp produced was known as ‘stuff’, and this was poured into a large vat where it was kept warm and agitated to ensure that the fibres in the stuff remained in suspension. It was here that the vatman produced individual sheets of paper by dipping a mould into the stuff and skilfully evenly draining off excess water as the mould was withdrawn to ensure an even layer of paper pulp. The mould consisted of a rectangular wooden frame with a mesh of closely woven wire. Once withdrawn from the vat the mould was passed to the coucher who tipped the wet sheet of paper over onto a piece of felt. The coucher built up a stack or ‘post’ of paper by adding new sheets of paper one-by-one until there were 144 leaves of paper in the post, each interleaved with felt to absorb the water. The completed post was then placed into a wet press by the coucher, who carefully squeezed out as much excess of water as possibly without overly distorting the paper sheets. The third man in the team, the layer, removed the sheets from the wet press and separated them out individually and hung each damp sheet over ropes which were raised into a louvered loft and left to dry. The final part of the process was to flatten the sheets in a press and polish them in a large finishing room called the ‘sale’ or ‘sol’. Quality writing and printing paper were coated with ‘size’ to prevent absorption of writing and printing inks. This was either done at the vat stage with size being added to the stuff, or later by dipping dry sheets into a tub of size. Papermaking was a slow painstaking process and hence paper was expensive, with white writing paper only affordable by the well-off. Each sheet of paper was pressed with a ‘watermark’ unique to the papermaker. This was formed by a wire design that was fixed to the mesh in the mould and left an exact copy of the design embedded into the paper fibres. Early writing papers were slightly uneven as the wires from the mould left ‘laid’ (horizontal) and ‘chain’ (vertical) lines on the surface. It wasn’t until the middle of the 18th century that James Whatman, a leading Kentish papermaker, developed a finer mould of fine woven wire leaves called a ‘wove’ which left only a slight impression which resembled fabric. The paper produced from a wove mould were much finer and easier to write on. Bank Note Paper Papermakers producing finer papers were called upon to produce bank note paper, a specialised process requiring considerable skill. One such papermaker in the Wey Valley became unwittingly embroiled in international intrigue which was an attempt to change the course of history. In 1793 Charles Ball had converted the corn mill on the Wey tributary, the Tilling Bourne in Albury, to manufacture bank note paper. This curious story is told by his grandson Charles Ashby Ball:

Notes: Modern Paper Terminology Much of the terminology and standard paper measurements of dimension and quantity we are familiar with today originated from the early days of papermaking. The ‘post’ of paper built up by the layer into a pile of 144 sheets was based on a common measure of quantity used at the time, a ‘dozen’ representing 12 units. A post had 12 dozen sheets which is referred to as a ‘gross’. Larger quantities were also measured in multiples of 12, where for example a ‘great gross’ representing 12 gross, consisted of 1,728 sheets of paper. Common measurements of paper quantities recorded as early as 1517 included: Many of the terms used to describe paper and card sizes sound quite quaint to us today, although many of these are still used for speciality papers. These include imperial, crown, foolscap, royal, large post, pinched post, cabinet, baronet, duke, diamond, court, rex, and duchess. Once folded in the printing and binding processes other terminology came into being: f° or fo = folio 2 leaves or 4 pages Paper size in terms of surface area follows a clear protocol standardised by an International Standard Organisation (ISO) system which gave us the A4 and A3 formats we tend to encounter in everyday life. This system, defined by ISO 216, has been adopted worldwide, with the notable exceptions of the USA and Canada who bizarrely still follow their own systems. The ISO system works on metric measurements and follows a simple doubling (as in the next size up is twice the size) or halving of areas. Prior to the adoption of the ISO system in 1975 different countries used a wild array of differing formats which made for extreme confusion, especially for those users who had to trade between international borders. Similarly ISO 269 defines envelope sizes ranging from C6 being the smallest to E4 the largest and each classified according to the folding of inserted standard paper sizes.

Modern Papermaking Modern society demands huge quantities of paper and this is manufactured on the whole from pulping wood taken from trees. Most species of trees have wood suitable for pulping, although certain species are preferred for their special qualities. Pulp from pine and spruce grown in Europe and North America have long been used in papermaking. The stages of paper production start with pulping the wood. Pulping can be achieved either by mechanically grinding down debarked timber into fibres using stone or metal surfaces, or by chemically breaking down wood chip. The next stage is to process the wood pulp into sheets of paper. Apart from now being undertaken by sophisticated machinery the process is not very different from that used by papermakers hundreds of years ago. The pulp is passed over a flat sieve to form a layer and is then pressed and dried. Additives are applied to produce different textures and colours. Political pressures have led to a dramatic increase in the manufacture of recycled paper, although in terms of overall output this still represents a low percentage. It is relatively simple to make your own recycled paper at home if you have a little space, the time and don't mind making a mess. Gather together old newspapers or other low quality paper which breaks down into a pulp easily, then follow these simple instructions:

You can get extremely inventive by mixing colours into the mix, or adding items such as wildflowers, grass or even fine orange peel to provide texture. Laying the drying paper pulp onto waxed paper will provide a smooth writing surface, or using cloth instead of newspaper as the drying base will take up the woven texture and embed this into your sheet of paper. © Wey River 2005 - 2012 |