|

HOME |

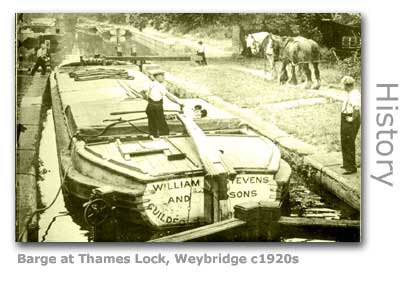

Life on the Barges The lot of a bargee and his family was not an easy one. Whatever the weather, cargoes had to be transported for if they weren't working there was no money to be had. And that also meant working through wars and risking attack, and also running the gauntlet of the navy's press-gangs and thieves determined to relieve the bargee of the goods he was carrying. |

Wey WEY BLOG WEY LIFE

click image to enlarge WATER LIFE WEY BLOG WEY BLOG |

|

||

|

The Last Bargemaster

Nancy Larcomber interviewed one of the last bargemasters who worked their craft between London and various towns along the Wey Navigations and the Basingstoke Canal during the early and mid part of the 20th century. Some of Captain Steve White’s accounts of life on the river have been quoted throughout this site, although I do recommend that you get hold of a copy of the full and far more expansive text as it makes for fascinating reading. This was published in 1995 by Towed Haul as Captain White’s River Life and is edited & illustrated by Nancy Larcomber. White started working on the barges at the age of twelve, and was officially on the haulier’s payroll at fourteen.

All Weathers - Many Dangers The barges were worked in all weathers throughout the year, and their voyages continued throughout the war. Such was the vital role that the barges played in moving essential commodities around the county in the last war that bargemasters like Captain White risked their lives to get through, surviving bombings and the random strafing of their craft by lone Luftwaffe fighter planes.

The early barge crews had a lot to contend with. Over and above the hard manual work and the discomfort of working the river especially during the bitter winter months, they were prey not only to a vagabond chancing his hand, but also to press gangs unofficially operated by the Admiralty. These gangs, which operated along the lower reaches of the Wey Navigation and along the Thames until as recently as 1815, were paid to seize able bodied men and present them to the Navy for service. Proprietors of the companies running barges up and down the Wey regularly had to petition the Admiralty to cease the attempts of the press gangs to kidnap their crews. At the end of the 18th century there were documented 35 applications made by barge owners to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to provide protection from this activity, which was not only terrifying the crews and their families but also jeopardising their businesses. Incredibly the Commissioners would only issue ‘protections’ for periods of 3 months which must have created considerable consternation at the time. The barge owners complained that when the petition had expired ‘the men have left their barges and secret themselves to avoid being pressed, whereby the trade is stopped to the very great detriment of the petitioners as well as the country in general.’

Carters & Bow-haulers Another breed of Wey Navigation professionals were the carters. Carters did not own or captain vessels but provided and led horses to tow the barges. Where horses weren’t available the barges had literally to be towed by hand. This tough job fell to the bow-haulers who worked together and could haul a fully laden barge from Stoke Lock in Guildford the 16 miles to Thames Lock at Weybridge leaving at 6.00 am and arriving at the Thames by 3.00 pm, a considerable achievement given the bulk and weight of the vessels they were hauling. Their job could become extremely hazardous if the weather turned and cross-winds and flooding resulted. The team would usually work with several bow-haulers hauling the barge and a single man working a rope downstream to minimise the effects of drift from cross-winds and flooding. A donkey or pony was often used on the stern for the same job. When water levels made use of the towpath hazardous, and when navigating the much broader River Thames, the barges were also poled and rowed if sails couldn’t be used or the barge wasn’t equipped. Each man would wield an 18 foot (5.5 metres) long oar.

Mechanisation saw the decline of the carters as coal fired and eventually diesel engines took the strain.

Confined Quarters The barges were equipped with a small living space and bunks. Captain White had the luxury of a feather bed which was fine as long as he managed to keep it dry and well aired. He, like other bargemasters, also had a small cooking range fired by coal and with rails around the top to stop pans and the kettle from falling off. A typical range of this type has been preserved in the galley of the Godalming Packet Boat Company’s vessel, the horse-drawn Iona.

© Wey River 2005 - 2012 |